Support our authors

DonateCountess Báthory and Blood-Drinkers: Part 2

As discussed in last week’s article, Countess Báthory of Hungary became infamous for supposedly killing hundreds of her servants and townsfolk. One of the most infamous stories connected to her was that she bathed in the blood of those innocents in order to keep herself alive. Her killing spree, if it actually happened, definitely sets her apart in European history. Was her supposed bloodbathing as transgressive to the Europe she lived in compared to how we see the act today, though? As it turns out, she was not the only blood-drinker in her time, and in fact there was a vibrant and well respected practice of the act alive and well at many strata of European society.

Consider that Countess Báthory existed in a time of contemporaries that were pushing Europe’s medical science into new regions. The Countess was born twenty years after the death of Paracelsus, the noted Swiss-German physician. By the time of her reign, Paracelsus’ methods would most likely have spread throughout Europe’s community of medical practitioners. One of Paracelsus’ suggestions for treatment involved the drinking of blood. As The Smithsonian states, “[t]he 16th century German-Swiss physician Paracelsus believed blood was good for drinking, and one of his followers even suggested taking blood from a living body. While that doesn’t seem to have been common practice, the poor, who couldn’t always afford the processed compounds sold in apothecaries, could gain the benefits of cannibal medicine by standing by at executions, paying a small amount for a cup of the still-warm blood of the condemned.”

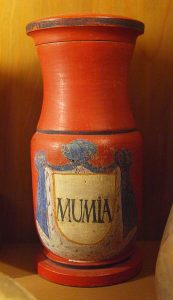

Paracelsus was and still is well-regarded as one of the focal points of modern medicine. He was not at all alone in his treatment decisions. Indeed, this field of medicine was broad enough to expand to the use of several bones and body parts for curative means. Known as “corpse medicine”, physicians and alchemists had several means of attempting to cure and strengthen bodies by creating broths and powders and tinctures made from the deceased. ““The question was not, ‘Should you eat human flesh?’ but, ‘What sort of flesh should you eat?’ ” says Sugg. The answer, at first, was Egyptian mummy, which was crumbled into tinctures to stanch internal bleeding. But other parts of the body soon followed. Skull was one common ingredient, taken in powdered form to cure head ailments. Thomas Willis, a 17th-century pioneer of brain science, brewed a drink for apoplexy, or bleeding, that mingled powdered human skull and chocolate. And King Charles II of England sipped “The King’s Drops,” his personal tincture, containing human skull in alcohol. Even the toupee of moss that grew over a buried skull, called Usnea, became a prized additive, its powder believed to cure nosebleeds and possibly epilepsy. Human fat was used to treat the outside of the body. German doctors, for instance, prescribed bandages soaked in it for wounds, and rubbing fat into the skin was considered a remedy for gout.”

These remedies just as often involved the direct imbibing of blood, however. According to Laphan’s Quarterly, “[t]he blood was typically harvested from the freshly dead, but could also be taken from the living. Such medicinal vampirism had no shortage of adherents: Marsilio Ficino, a highly respected fifteenth-century Italian scholar and priest, said that elderly people hoping to regain the spring in their step should “suck the blood of an adolescent” who was “clean, happy, temperate, and whose blood is excellent but perhaps a little excessive.” Another popular remedy, sometimes attributed to Saint Albertus Magnus, involved distilling the blood of a healthy man as if it were rose water; the result was said to cure “any disease of the body,” and “a small quantity…restoreth them that have lost all their strength,” according to one 1559 text. By the 1650s there was a general belief that drinking fresh, hot blood from the recently deceased would cure epilepsy, as well as help with consumption. Meanwhile, dried and powdered blood was recommended for nosebleeds or sprinkled on wounds to stop bleeding.”

This definitely does not mean that Europe was full of depraved lunatics like the Countess was asserted to be. It is just possible that Bathory was tapping into a field of medicine that had some legitimacy at the time and using the byproduct of her supposed killings to self-medicate. It is interesting to note that not only did this field of medicine start before her death, but that it carried on far beyond it. In a sense, the mental scar she wrought on the public consciousness that failed to disappear as the centuries went by was an extrapolation of an industry based around death. Corpse medicine relied on exploiting the increased mortality rate that came with living before modern medicine. If the death of another meant that someone else’s life would be saved, then Báthory’s blood baths could be considered cutting out the middle men that were natural causes or state-sanctioned execution.

After being arrested, Báthory would never see trial and die in a jail cell in 1614. Meanwhile, corpse medicine would continue to rage on. The Smithsonian states that, “In 1847, an Englishman was advised to mix the skull of a young woman with treacle (molasses) and feed it to his daughter to cure her epilepsy. (He obtained the compound and administered it, as Sugg writes, but “allegedly without effect.”) [ . . . ] Mummy was sold as medicine in a German medical catalog at the beginning of the 20th century. And in 1908, a last known attempt was made in Germany to swallow blood at the scaffold.” The memory of her story lived on with the practice of a ghoulish attempt to stave off death, with only an ethical boundary between the basin of young blood and the physician’s potion.

Interestingly enough, we have a possible example of corpse medicine on the rise in the present day. In America, a start-up company called Ambrosia is looking to provide wealthy individuals with the blood of young individuals paid for their pints. The owner points to studies that show the rejuvenative quality of blood… Business Insider states that, “In 2017, Ambrosia enrolled people in the first US clinical trial designed to find out what happens when the veins of adults are filled with blood from the young. While the results of that study have not yet been made public, [Jesse] Karmazin told Business Insider the results were “really positive.” [ . . . ] There appears to be significant interest: since putting up its website last week, the company has received roughly 100 inquiries about how to get the treatment [ . . . ]”